Editor’s note: This article is part of “We the Immigrants,” a Community Based News Room (CBNR) series that examines how immigrant communities across the United States are responding to immigration policies. The five-part series is supported by a Solutions Journalism Network’s Renewing Democracy grant.

Navneet Kaur, from Salem, Ore., was part of a team of 56 to 60 drivers from the Post Detention Respite Network who waited in shifts outside the federal prison in Sheridan to pick up detainees after they’d been released. “It shocked me because it’s not part of the country where people would send detainees,” she said. “Reflexive action was to jump in and help in whatever way I could.”

Kaur is a Sikh from Punjab, India, and also provided translation services. She has been in the United States for 18 years, and in Oregon for 15. She is a member of the Sikh Center in Salem, where many of the detainees found shelter following their release.

The Sheridan detainees were first apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border and transferred to prison in Sheridan in late May. While not all the detainees were South Asian—some were from Guatemala, Mexico and China—the recent plight of South Asian asylum seekers has been kept out of the public consciousness.

According to the Willamette Week, “U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement placed the men in the federal prison because the federal immigration agency ran out of space in its detention centers designed to house asylum seekers and other immigrants who have not been convicted of a crime.” About half of the detainees are from India, and many from the Sikh tradition.

Sikhs first immigrated to Oregon (mostly via Vancouver, British Columbia) around 1905, escaping British colonialism that ravaged India. Queen Victoria had declared their equal status with Britain, no matter where they traveled, but they didn’t experience this equality in the States. Many relocated to Oregon from California and Washington, due to Oregon’s quasi-peace with Indian laborers.

“Oregon started a specific social pact, starting with the Chinese laborers in the late 1800s, and then extending to Indians and Filipinos, that called for racial peace in order to ensure a labor force,” states Johanna Ogden, an independent historian. “Of course, that didn’t hold.”

With the advent of the First World War, Indians in America saw an opportunity to return to their homeland and fight for independence. The Hindustani Association of America was formed in Portland, Ore., in 1912, and a second chapter was started in the small town of Astoria. By 1913, the members had shifted their mission from sponsoring Indian youth in America to returning to India themselves and forming a United States of India.

Ogden provides detail in her Oregon Historical Society article, “Ghadar, Historical Silences, and Notions of Belonging.“ She writes, “From March 31 through April 14, 1913, local men and others traveling from Portland and St. Johns gathered in Bridal Veil (twenty men), Linnton (one hundred men), and Winans, a whistle stop in the woods south of Hood River (one hundred men). By late spring, they were ready for the culminating meeting in Astoria.”

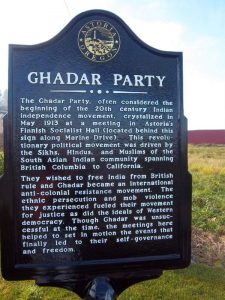

The Ghadar rebellion—seizing India back from British rule—was officially proposed and passed at this meeting. This political action resulted in a mass exodus of Indians from Oregon. Small pockets remained, though most who didn’t return to India migrated to British Columbia and California. While ultimately unsuccessful, Ghadar was instrumental to India later gaining self-governance.

This important history was erased until the publication of Ogden’s research.

“No one knew until Johanna published her article, and until the city council of Astoria decided to celebrate the Ghadar Centennial,” Kaur says. “Even in the history books of India, there is no mention of Ghadar’s roots in Astoria.”

Now, the Ghadar Party history will soon be taught in Oregon public schools, marking a step toward better representation.

In 1923, another political event prompted a change to national policies in the United States. Bhagat Singh Thind, a Sikh from Punjab, applied for citizenship after fighting for the U.S. in World War I. Such citizenship had been promised to him, as well as millions of other immigrant soldiers. Thind received and lost his citizenship in Washington and Oregon, with his case making its way to the Supreme Court. Since the Naturalization Act of 1906 restricted citizenship to only “free white persons” and people of African descent, Thind argued in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind that since Aryans had invaded Punjab and subsequently intermixed, he possessed Aryan blood as a high-caste Hindu. The court denied his appeal, changed its racial classification of Asian Indians, and denied and revoked a plethora of naturalization certificates.

With the Refugee Act of 1980, Sikhs once again settled in rural Oregon, as well as in other parts of the country. Though the Sikh community was relatively unaware of their prior history in the region, their local presence was invaluable in aiding the Sheridan detainees, many of whom needed translation assistance. A complete lack of common language between detention employees and those detained added to the already deplorable conditions inside the cells.

“Those early days had been bleak, the migrants said,” according to The Oregonian. “There were housed three-to-a-cell, sharing a common toilet, and restricted to their quarters 22 hours a day.”

The Innovation Law Lab—a nonprofit in Portland, Ore., that helps attorneys win tough immigration cases—has been able to take over 90 Sheridan cases pro bono thus far. This work came after the Oregon ACLU won a lawsuit of habeas corpus in federal court, declaring the prison detainment conditions unconstitutional. Before President Trump’s Executive Order 13769 of 2017, colloquially known as the Muslim ban or travel ban, immigrants had access to lawyers and worked with U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to process applicable paperwork.

“That’s how things worked in the past,” Kaur explains. “You passed your credible fear, you’re out, and your case goes on, for however long it goes on. But that didn’t happen this time.”

Indefinite detention without representation is not a new problem. Suman Raghunathan, executive director at South Asian Americans Leading Together (SAALT) works to amplify South Asian immigrant voices in the U.S.

“We are seeing a rising tide in South Asian detainees over the last four or five years,”she says, “spanning individuals originally from India (largely Sikhs, in our experience), Bangladesh and most recently a wave of Nepalis. Many of these folks are fleeing political and/or religious persecution and/or discrimination in South Asia and making the decision to, in some cases, make the arduous crossing through Latin America and cross the U.S.-Mexico border.”

In 2015, detainees in Florida, Alabama and Orange County (Calif.) participated in hunger strikes to protest being denied basic rights, such as translators and timely credible fear interviews. During April and May this year in Georgia, migrants at the Stewart Detention Center also participated in hunger strikes, while migrants at the Folkston Detention Center did the same in June. Both of the Georgia detention centers are for-profit and located in remote areas, just like Sheridan.

Vân Huynh, a supervising immigration attorney with Advancing Justice-Atlanta, notes the challenges the detainees in Georgia face. “It’s much more difficult for them to be able to send documents, or gather documents from their families to support their case,” she says. “Given just how remote those areas are, being able to get access with them and get a base of attorneys to even contact is really difficult.”

(ACLU Oregon / Twitter)

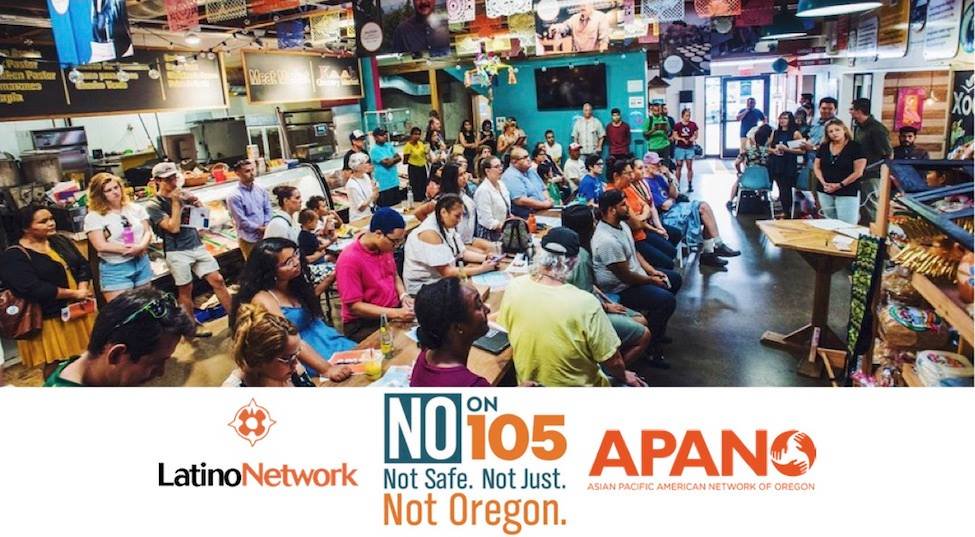

In Oregon, nonprofits worked together with the Sikh community to aid the Sheridan detainees. The Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon (APANO) partnered with Innovation Law Lab to provide legal counsel. Their success was due to the combined efforts of not only advocacy groups, but also community members of different faiths.

According to Raghunathan, “Jai [Singh of APANO], who is Sikh American, was instrumental in coordinating and leveraging broader support from the local Oregon Sikh and South Asian community and played a crucial role in mobilizing Oregon gurdwaras [places of worship for Sikhs] to help provide some translation and interpretation, as well as support from local religious leaders. In a combined effort, the community rallied for, housed, fed, clothed and transported the detainees as they were released.”

The Rev. Ron Warner Jr., a Lutheran pastor and organizer with the Interfaith Movement for Immigrant Justice (IMIJ) in Portland, Ore., has been advocating for immigrant rights the past 12 years. “We are made up of about 140 faith communities around the whole state of Oregon from many different faith traditions,” he says.

Volunteers with IMIJ protested at Sheridan and the ICE headquarters. Christians moved their worship service outside the detention center in protest of Jeff Sessions’ use of the Bible to defend the lockdown on immigration. Churches in Yamhill County provided clothing, and the Beaverton temple raised money to buy more. Respite centers were set up at the Salem and Beaverton temples.

Jai Singh lists the following APANO accomplishments, which the community helped come to fruition:

- Developed a “Post Detention Respite Network Toolkit” that has been helpful for the legal response for the release of over half the asylees.

- So far transferred $100 each to 82 asylees and $50 to three asylees, totaling slightly over $9,100.

- Purchased airfare for one of the asylees to connect with his new sponsor in Los Angeles, Calif.

- Distributed over 20 boxes of tangible resources, donated by volunteers that APANO has mobilized, to the Sheridan Post Detention Respite Network for asylees, including over $1,000 worth in gift cards and calling cards.

- Attended over four vigils and direct action events in solidarity with other grassroots organizations to bring attention to the unjust detention of Sheridan asylees.

- Mobilized over 200 individuals to contact their public officials to put pressure on releasing asylees.

- Helped raise and collect over $15,000 from donors to assist with the post-detention work as well as commissary funds.

At this time, all but three of the detainees have been released.

The town of Sheridan, Ore., is a small pocket in Yamhill County with 6,127 residents (as of the 2010 census). Only 2.4 percent of them are Asian descent. Though the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown has filled federal immigrant detention centers to capacity, it is not known why the detainees were sent so far north after being apprehended at the border. It’s also unknown why Sheridan itself was chosen for their literal incarceration.

If the goal was alienation from a city center, the plan failed. The strong Sikh community in Yamhill County and the surrounding counties sprang into action to support the organizational efforts. Community action is often critical for swift civic change.

“Many South Asian or AAPI community-based organizations lack the capacity to coordinate broader legal services, representation, and referral efforts that are bolstered by local community action capacity,” says Raghunathan. “We’ve found this matrix of community power is crucial to effectively respond to detentions on the ground.”

ICE may have been unaware of the strong East Indian/Sikh presence, or at least undeterred by it.

Whatever the reason, the effects of detention are the same and can create a cycle of silence for immigrants. Their voices go unheard, so firsthand accounts of injustice and dehumanization are not shared. Multiple attempts to speak to Sheridan detainees for this story were unsuccessful. Folks are reluctant or now dispersed.

Socially, stories about who resides where and what histories matter are fraught with conscious and unconscious biases. In Ogden’s article, she discusses the politics of collective memory: “Historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot stresses a critical feature of this process we call history. … His approach is to examine our narratives as an insight into our beliefs and relations of power. Applying that perspective here, what is the narrative that has supplanted the Punjabis and Ghadar from our collective memory? What are the stakes of this narrative omission in the present?”

In part, the stakes are the intolerance that comes from misinformation.

“The biggest roadblocks for us have been fear on a large level, and fear on a small level in our local communities, where people don’t understand, or believe myths about immigration and migration,” Warner says. “The level of othering and denigrating of other human beings feels like it’s at an all-time high right now.”

Warner believes that faiths working together is in line with various religions’ belief systems: “A lot of our sacred stories at the end of the day both reveal something about the divine, but also about what it means to be human. In a time where fear has dictated so many of our policies, we are trying to raise up or lift up humanity over fear.”

Is it working?

“Many people ask me why and how I got involved in this project,” Kaur says. “And I have no answer to that. It’s just an automatic response for me, because we’re not supposed to sit in judgment. If somebody needs help, you give them help. That’s what my faith tells me to do.”

Broader Asian American organizations also are working to change policies for asylum seekers. “The South Asian community has elevated this issue before congressional members,” says Huynh. “A couple months ago, the National Immigration Project, with the National Lawyers Guild, presented their findings.”

While outreach in Sheridan has been successful, one can only hope about the future. “It’s hard to be living in a time when despite our best efforts and our incredible organizing and so many wonderful hearts and minds working on things like this, there may be a new policy that comes down next month that undoes all of it,” Warner states.

In fact, the Trump administration wants to limit asylum seekers with a new rule, and there was a measure on the Oregon ballot to repeal Oregon’s state sanctuary law, which did not pass in the recent elections. The organization behind the measure, Oregonians for Immigration Reform, is considered a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center. Despite its public reputation, Oregon has a long history of racial exclusion, including a strong white supremacist presence.

While equality measures are always in flux, Warner has a tactic to remain hopeful.

“For us in the faith community, one of the big learnings from this summer is the means have to be the ends,” he says. “It can’t just be about the outcomes, but the very ways we organize together and the relationships that we build all have to have a long-haul dimension to them. And that’s where we’re finding healing and hope springing forth amidst the heartbreak.”

Our Community Based News Room publishes the stories of people impacted by law and policy. Do you have a story to tell? Please contact us at CBNR at CBNR. To support our Community Based News Room, please donate here.

You can find this piece at the LA Progressive at: https://www.laprogressive.com/south-asian-asylum-seekers/